Reasonable Suspicion

"Reasonable Suspicion:" Less than "probable cause," but more than no evidence (i.e., a "hunch.") at all.

back to top

Defined

Defined: "Reasonable suspicion" is information which is sufficient to cause a reasonable law enforcement officer, taking into account his or her training and experience, to reasonably believe that the person to be detained is, was, or is about to be, involved in criminal activity. The officer must be able to articulate more than an "inchoate and unparticularized suspicion or hunch' of criminal activity." (Terry v. Ohio (1968) 392 U.S. 1, 27 [20 L.Ed.2nd 889, 909].)

"Because the balance between the public interest and the individual's right to personal security,' [Citation] tilts in favor of a standard less than probable cause in such cases, the Fourth Amendment is satisfied if the officer's action is supported by reasonable suspicion to believe that criminal activity "may be afoot,"' (United States v. Sokolow (1989) 490 U.S. 1, 7 [104 L.Ed.2nd 1, 10]; quoting Terry v. Ohio, supra, at p. 30 [20 L.Ed.2nd at p. 911].)

back to top

Articulable Objective Suspicion

Articulable Objective Suspicion: A detention, even if brief, is a sufficiently significant restraint on personal liberty to require "objective justification." (Florida v. Royer (1983) 460 U.S. 491, 498 [75 L.Ed.2nd 229, 236-237].)

Reasons which an officer feels give him or her reasonable suspicion to detain must be articulated, in detail, in an arrest report and later recounted in courtroom testimony.

An officer's inability to articulate those suspicious factors that give rise to the need to stop and detain a suspect is one of the more common causes of detentions being found to be illegal.

back to top

A Hunch

A Hunch: An officer's decision to detain cannot be predicated upon a mere "hunch," but must be based upon articulable facts describing suspicious behavior which would distinguish the defendant from an ordinary, law-abiding citizen. (Terry v. Ohio, supra.)

"A hunch may provide the basis for solid police work; it may trigger an investigation that uncovers facts that establish reasonable suspicion, probable cause, or even grounds for a conviction. A hunch, however, is not a substitute for the necessary specific, articulable facts required to justify a Fourth Amendment intrusion." (Italics added; People v. Pitts(2004) 117 Cal.App.4th 881, 889; quoting United States v. Thomas (9th Cir. 2000) 211 F.3rd 1186, 1192.)

A stop and detention based upon stale information concerning a threat, which itself was of questionable veracity, and with little if anything in the way of suspicious circumstances to connect the persons stopped to that threat, is illegal. (People v. Durazo (2004) 124 Cal.App.4th 728: Threat was purportedly from Mexican gang members, and defendant was a Mexican male who (with his passenger) glanced at the victim's apartment as he drove by four days later where the officer admittedly was acting on his "gut feeling" that defendant was involved.)

Seemingly innocuous behavior does not justify a detention of suspected illegal aliens unless accompanied by some particularlized conduct that corroborates the officer's suspicions. (United States v. Manzo-Jurado (9th Cir. 2006) 457 F.3rd 928; standing around in their own group, conversing in Spanish, watching a high school football game.)

Observing defendant sitting in a parked motor vehicle late at night near the exit to a 7-Eleven store parking lot, with the engine running, despite prior knowledge of a string of recent robberies at 7-Elevens, held to be not sufficient to justify a detention and patdown. (People v. Perrusquia (2007) 150 Cal.App.4th 228.)

back to top

The Totality of the Circumstances

The Totality of the Circumstances: The legality of a detention will be determined by considering the "totality of the circumstances." (United States v. Arvizu (2002) 534 U.S. 266, 273 [151 L.Ed.2nd 740, 749]; see also People v. Dolly (2007) 40 Cal.4th 458.)

"All relevant factors must be considered in the reasonable suspicion calculus-even those factors that, in a different context, might be entirely innocuous." (United States v. Fernandez-Castillo (9th Cir. 2003) 324 F.3rd 1114, 1124, citing United States v. Arvizu, supra, at pp. 277-278 [151 L.Ed.2nd at p. 752].)

back to top

The Officer's Subjective Conclusions

The Officer's Subjective Conclusions: Whether or not an officer has sufficient cause to detain someone will be evaluated by the courts on an "objective" basis; or how a reasonable person would evaluate the circumstances. The officer's own "subjective" conclusions are irrelevant. (Whren v. United States (1996) 517 U.S. 806 [135 L.Ed.2nd 89].)

back to top

A Seizure

A Seizure: Although a detention is a "seizure" under the Fourth Amendment (Terry v. Ohio, supra, at p. 19, fn. 16 [20 L.Ed.2nd at pp. 904-905].), it is allowed on less than probable cause because the intrusion is relatively minimal and is done for a valid and necessary investigative purpose.

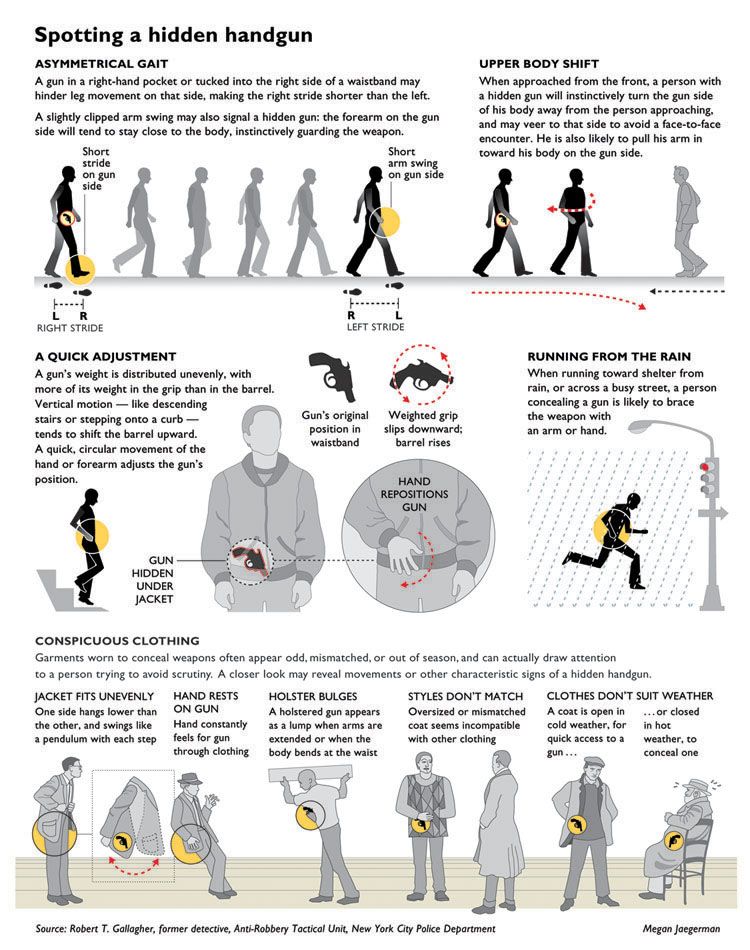

And note P.C. § 833.5, providing a peace officer the authority to detain for investigation anyone who the officer has "reasonable cause" to believe illegally has in his or her possession a firearm or other deadly weapon.

back to top

Probable Cause vs. Reasonable Suspicion

Probable Cause vs. Reasonable Suspicion: The occasional inarticulate judicial references to the need to prove "probable cause" (e.g., see United States v. Willis (9th Cir. 2005) 431 F.3rd 709, 715, referring to the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Whren v. United States (1996) 517 U.S. 806 [135 L.Ed.2nd 89].) was not intended to raise the standard of proof from one of needing only a "reasonable suspicion." (United States v. Lopez (9th Cir. 2000) 205 F.3rd 1101-1104.)